VINCENT

|

||||||||

|

How the Vincent family came to North Hill is uncertain. In his book "Trebartha - The House By The Stream" Bryan Latham writes: "The Vincent family seat was at Stoke Dabernon in Surrey. A Vincent married an heiress from the Batten family in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and so got possession of Battens. ... Tradition has it that in the reign of James I a Vincent wife eloped, taking with her all the family jewels, and misfortune overtook the family." As can be seen on the transcript of document #149 of The Cartulary of Launceston Priory, as discussed on the page about Battens, the surname of Batyn/Battens seems not have lasted long after the end of the 14th century and there is no mention of a Vincent family. The marriage of a Vincent to a Battens descendant seems unlikely. If the tale of the elopement has any foundation this is likely to have been one of the daughters of Thomas Vincent shown on the tomb in St Torney's Church. | ||||||||

| ||||||

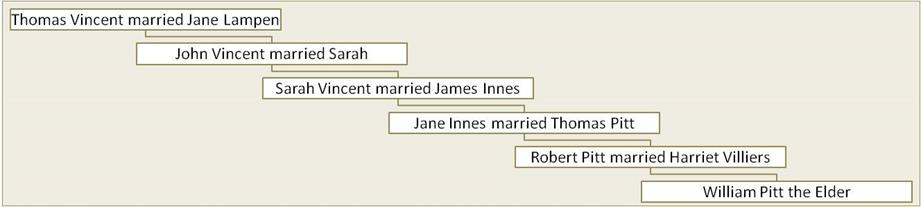

Thomas Vincent (died 1607)Thomas Vincent was a landowner, farmer and attorney at law. He married Jane Lampen in the early 1580s and they had fifteen children. Jane's mother was Jane Lower, whose family lived at Padreda in Linkinhorne. |

|

The Vincent Tomb |

|

|

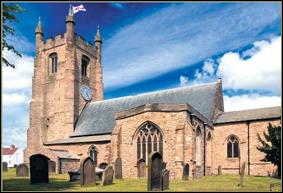

The Vincent family are remembered by the unique and elaborate incised slate tomb in the north west corner of the nave of St Torney’s Church shown below. IN earlier times it stood in the chancel. It is likely that Thomas Vincent senior began the process of commissioning the tomb upon the death of his wife in 1602 [this was before the calendar change when the new year began on March 25th explaining why the tomb gives the date of 1601] and the process was finalized by his sons Thomas and John. The dedication which is on the table section of the tomb reads: “Here lye the bodies of Thomas Vyncent, Gentleman and Jane his Wife, by whom he had issue 8 sonnes and 7 daughters. He departed this life ye 29th March 1606. She ye 7th of Januarie 1601.”

|

Video

|

|

It also has a Latin inscription as follows:

|

|||||

Also on the back plate Death is pictured holding a scythe and a dart, pictured right. Below him kneels Thomas Vincent and his wife with their sons and daughters. Elements of the Danse Macabre are not uncommon on tombs. Sophie Oosterwijk writes of Thomas Vincent’s tomb in Death and Danse Macabre Iconography in Memorial Art: |

|

The front panel of the tomb shows three coats of arms, two with crests; |

Lampen (left) - argent, on a bend engrailed sable, three ram’s heads cabossed of the field attired or Vincent (centre) – azure, three quatrefoils argent Lower (right) – sable, a chevron between three roses argent |

John Vincent (c1591-1646)

|

|

John Vincent (c1630-1710)

John's second wife was an Elizabeth. They married about 1660 but details of her family and the location have not survived. Elizabeth died in 1677, shortly after the birth of their last child. John died in 1710. Both were buried at St Torney's, North Hill. They had the following children, all of whom were baptised and buried in St Torney's, North Hill:

Perhaps John was prompted into resolving his own affairs by his involvement with his daughter, Elizabeth's, dispute with her children. In 1708 John put in place a legal instrument to safeguard his immediate future, the medium term future for his daughter, Sarah, and the longer term future of his grandchildren. John lived in Battens with Sarah, her husband Theodore Darley and their children. John transferred the ownership of his property to his friends Stephen Revell and Robert Coombe for Sarah's "support and livelihood". The friends would have been trustees and it was their responsibility to ensure that Sarah was properly financially maintained. The property transferred was: "Moiety [part share] of manor of Trewithie, and half the moiety of manor of Rillaton Peverell; moiety of tenement of Battens, Adacroft, Bowda, North Hill churchtown, Treswell, Tresellern, Lanxton and Trekernell in North Hill and St Juliot; also one part of Twelve Men's Moor". This ensured that his estate was not wholly lost to the family. Depending upon circumstances it may have been possible for the feuding Aclands to lay a claim, it may have been possible for any future husband of his daughter Elizabeth to make a claim and even for John's own nephews and nieces to make a claim - but not now he had given away his estate. As far as is known, John left no will and died intestate. His daughter, Elizabeth, was supposed to administer his residual estate but failed to do so, as there wasn't much apparent need any more. When Elizabeth Acland died in London it was left to her sister, Sarah Darley, to deal with Elizabeth's and John's estates but she didn't. When Sarah died her husband Theodore was supposed to deal with Sarah's estate and by extension, Elizabeth's and John's estates as well. Inertia struck and he didn't. It wasn't until Theodore died in 1743 that his son, Vincent Darley started the process of tidying up this legal morass. This led to or exacerbated disputes within the Darley family that were to take decades to resolve. |

Thomas Vincent (1634-1678)Thomas' biography has been taken from the "A Puritan's Mind" website: Thomas Vincent (1634-1678) was an English Puritan Calvinistic minister and author. He was the second son of John Vincent and elder brother of Nathaniel Vincent (both also prominent ministers), was born at Hertford in May 1634. After passing through Westminster School, and Felsted grammar school in Essex, he entered as a student at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1648, matriculated 27 February 1651, and graduated with a B.A. March 16, 1652, and an M.A. June 1, 1654, when he was chosen catechist. Leaving the university, he became chaplain to Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester. In 1656 he was incorporated at Cambridge. He was soon put into the sequestered rectory of St. Mary Magdalene, Milk Street, London (he was probably ordained by the sixth London classis), and held it till the Uniformity Act of 1662 ejected him. He retired to Hoxton, where he preached privately, and at the same time assisted Thomas Doolittle in his school at Bunhill Fields. During 1665, the year of the Great Plague of London, he preached constantly in parish churches. He said of the Great Fire of London (1666), "And if Monday night was dreadful, Tuesday night was more dreadful, when far the greatest part of the city was consumed: many thousands who on Saturday had houses convenient in the city, both for themselves, and to entertain others, now have not where to lay their head; and the fields are the only receptacle which they can find for themselves and their goods; most of the late inhabitants of London lie all night in the open air, with no other canopy over them but that of the heavens: the fire is still making towards them, and threateneth the suburbs; it was amazing to see how it had spread itself several times in compass; and, amongst other things that night, the sight of Guildhall was a fearful spectacle, which stood the whole body of it together in view, for several hours together, after the fire had taken it, without flames, (I suppose because the timber was such solid oak,) in a bright shining coal as if it had been a palace of gold, or a great building of burnished brass." His account of the plague in "God’s Terrible Voice in the City by Plague and Fire," 1667, is graphic; seven in his own household died. Subsequently he gathered a large congregation at Hoxton, apparently in a wooden meeting-house, of which for a time he was dispossessed. He was among the signers of the 1673 Puritan Preface to the Scots Metrical Psalter. He did not escape imprisonment for his nonconformity. He died on October 15, 1678, and was buried (October 27) in the churchyard of St Giles-without-Cripplegate. His funeral sermon was preached by Samuel Slater. |

Nathaniel Vincent (1638-1697)

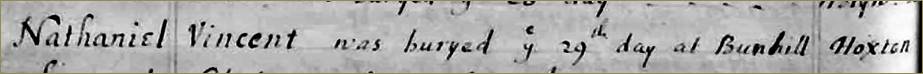

Nathaniel also features in the “Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 58 page 360” an extract from which is shown, right. Nathaniel died at his home in Hoxton just outside London and was buried in Bunhill Fields cemetery in Moorgate, London on the 29th June 1697. In 1665 the City of London Corporation decided to use some of the fen or moor fields, known as Bunhill Fields in Finsbury to this day, as a common burial ground for the interment of bodies of inhabitants who had died of the plague and could not be accommodated in the churchyards. The burial ground attracted mainly dissenters from the Established Church who were of a Protestant persuasion, partly owing to their much larger numbers in the locality. The entry below has been taken from the registers of St Leonard’s in Shoreditch. |

Sir Matthias Vincent (c1645-1687)

|

The images at the top of the page show (L-R): Vincent family arms; skeleton detail from the Vincent tomb in St Torney's Church, North Hill; backplate of Vincent tomb. |

The upper part of the back plate shows an angel stamping on death and a serpent indicating the victory over evil.

The upper part of the back plate shows an angel stamping on death and a serpent indicating the victory over evil.

John (c1630-1710) inherited Battens in North Hill when he was about 16 years of age, upon the death of his father. Initially supported by another member of the family, probably his Great Uncle George Vincent (c1600-1662), John farmed the land until his own death in 1710. He married twice. His first wife was the spinster Mary Spoure (1627-1662), whom he married in North Hill in 1661. They had a daughter, named Mary about whom nothing else is known. It is likely that baby Mary's birth contributed to the death of her mother just a few months later. Mary Spoure was the sister of

John (c1630-1710) inherited Battens in North Hill when he was about 16 years of age, upon the death of his father. Initially supported by another member of the family, probably his Great Uncle George Vincent (c1600-1662), John farmed the land until his own death in 1710. He married twice. His first wife was the spinster Mary Spoure (1627-1662), whom he married in North Hill in 1661. They had a daughter, named Mary about whom nothing else is known. It is likely that baby Mary's birth contributed to the death of her mother just a few months later. Mary Spoure was the sister of  Nathaniel was baptised in North Hill in 1638. At the time his father and the family were moving from parish to parish because his father's puritan teachings did not generally meet the approval of the parishioners. Nathaniel was, like his father John and brother Thomas, a non-conformist minister. He achieved some notoriety for his beliefs and was imprisoned several times. Some of his treatises were written whilst imprisoned.

Nathaniel was baptised in North Hill in 1638. At the time his father and the family were moving from parish to parish because his father's puritan teachings did not generally meet the approval of the parishioners. Nathaniel was, like his father John and brother Thomas, a non-conformist minister. He achieved some notoriety for his beliefs and was imprisoned several times. Some of his treatises were written whilst imprisoned.