DARLEY

| ||||||||||||

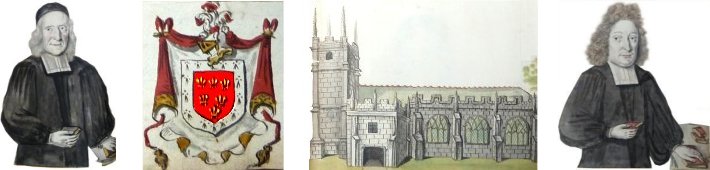

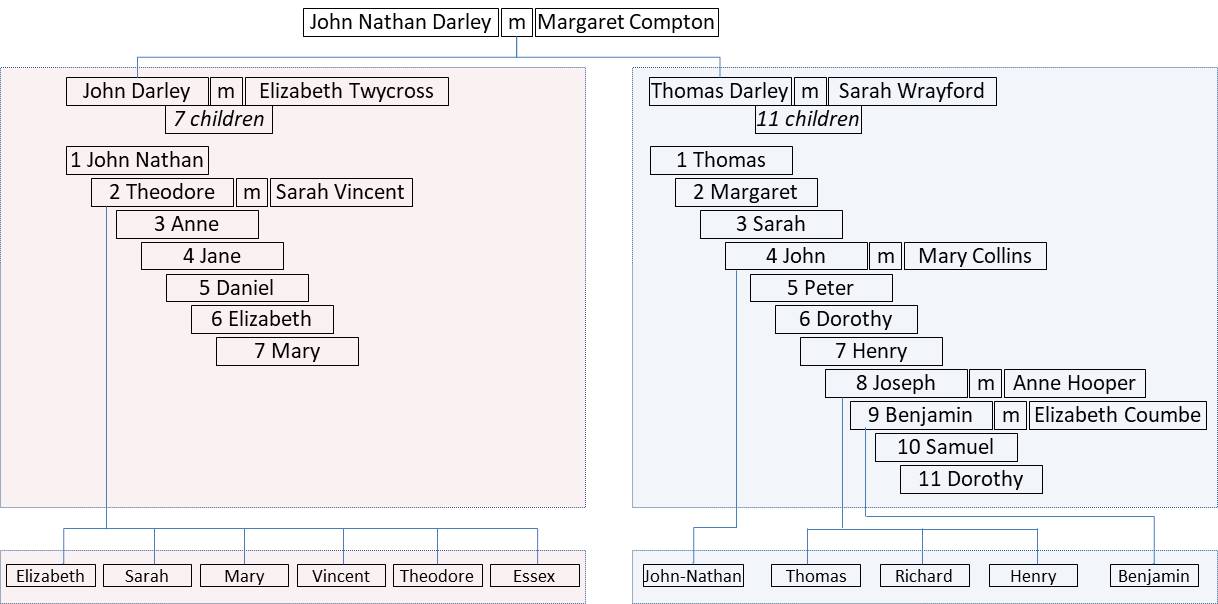

John Darley jnr (1648-1708) - Rector of St Torney's from 1699 to 1708

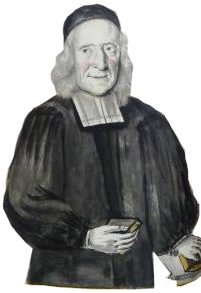

Their eldest, John-Nathan, went to Oxford University and earned his BA in 1695 but no more is known about him. Their second son, Theodore, married Sarah Vincent of Battens. Jane, their second daughter, married the Reverend John Roberts who was Rector of North Hill from 1716 to 1748. John Darley died in 1708 and was buried in St Torney's. Elizabeth died on 14 March 1724 and at her burial is recorded as "patroness of North Hill". John's estate passed to his son Theodore (1675-1743). The image of John Darley (click for a larger image) has been taken from The Book of Spoure. |

Theodore Darley snr (1675-1743) and his wife Sarah (nee Vincent, 1674-1737)Theodore Darley was the son of John Darley and Elizabeth Twycross. Born in 1675 he married at the age of about 18 to Sarah the daughter of John Vincent of Battens. They had eight children but two, both named Frances, died in infancy. The remaining six children are shown in the family tree above. Theodore was a qualified attorney at law and his two sons, Vincent and Theodore, followed in his footsteps and became similarly qualified. Sarah's elder sister, Elizabeth, had married the widower Richard Acland about 1700. She probably took a substantial dowry with her to the marriage, provided by her father John Vincent. Elizabeth's marriage was short and childless as she was widowed about 1702. A series of legal cases between the Vincents and the Aclands ensued because Richard's children, by his first marriage, believed they were entitled to the dowry as it formed part of their father's estate. John Vincent disagreed and to ensure that the Aclands would have no claim on his estate he conveyed, through his "natural love and affection" all his property to his second daughter, Sarah, in 1708. John Vincent died in 1710 without having written a will, presumably because he had little left to bequeath. Sarah died in 1737 and her husband, Theodore, died in 1743. Theodore wrote his will on 27 August 1743 and by 14 September he was buried at St Torney's. His estate was not inconsiderable. It included Battens, tenements in Lake and Gospelhead, livestock, mortgages, money and personal effects. His two sons clashed over the will's contents. Vincent, being the eldest son, received the bulk of the estate. Theodore jnr, the second and youngest son, received one shilling. The Bequest of One Shilling. |

Vincent Darley (1703-1764)Vincent Darley, the eldest son of Theodore Darley snr, was baptised in St Torney’s Church on 14th March 1703. Vincent had no children of his own. In 1744 he married Elizabeth, the widow of George Newton who had died in 1731, leaving Elizabeth with two daughters - Elizabeth and Margaret.

In his lifetime, Vincent was an active member of the community. As a member of the gentry he held lands which he leased to tenants and this social position enabled him to take up offices in both church and community. There are over 50 documents in the Cornwall Record Office (Kresen Kernow) in Redruth which bear his name. Most are land transactions but others evidence his position as a gentleman and show him upholding the law through his representations at the Quarter Sessions.

He was buried in St Torney's three days later, the terms of his will saying:

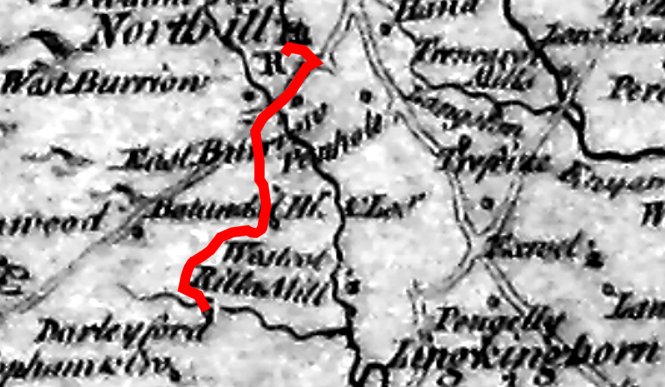

This plaque is on the north wall of St Torney's and reads After Vincent’s death a ‘ghostly’ story was put about regarding his haunting of the road we now know as the B3254 from Darley Ford to North Hill village. The story of Vincent’s apparition, frequently as a black dog, was detailed by Barbara C Spooner in 1926 and is repeated below. |

Theodore Darley jnr (1705-1776)Theodore was Vincent's only brother. He was 2 years younger and they were probably locking horns from a young age. When their father died in 1743 Vincent was living in Callington and Theodore was in Battersea, now part of London. Like their father, both brothers were attorneys at law and Theodore practiced out of Clements Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery that formed part of the prestigious Inner Temple. Theodore had seven children with his wife, Anne. Three of these children were alive in 1743, William aged 3, Utritia aged 2 and Cassandra aged 1, but none was mentioned in their grandfather's will. The slight of his children not being recognized would only enrage Theodore, particularly as he himself was only granted one shilling in the will. Theodore unsuccessfully contested his father's will which deepened the family dispute. Theodore died in the summer of 1776 but no record has survived to tell us where he died or where he is buried. In his will he left the following unusual instruction: "I do hereby desire that I may not be buried within a Fortnight after my Death but be kept in an open coffin so long as possible" He was unlikely to have been buried in North Hill where the registers are quite comprehensive. It is more likely that he died in Bovingdon in Hertfordshire where his son William lived, or in his accommodation in the Inns of Court in London. He left almost all his estate to his son William who never took up residence in North Hill. |

The DisputeThe Cause of the Dispute. We don't know when the dispute between the brothers Vincent Darley and Theodore Darley jnr began, and what started it, but the underlying issue was money. Both Vincent and Theodore jnr were qualified attorneys at law, explaining the manner in which the family dispute was conducted through the courts and, therefore, open to public gaze. For half of the 18th century the Darley family were both plaintiffs and defendants in legal cases against one another, details of which are to be found in The National Archives. The following is a timeline through the dispute. 1710 to 1743 - Adminstration of Estates. John Vincent, father of Sarah Darley, died intestate in 1710. It was, therefore, the responsibility of his daughter, Elizabeth Acland, to wind up the estate of her father, but she failed to do this. When she died in 1733 in London it was left to her only surviving relative, her sister Sarah Darley, to deal with both Elizabeth's and their father's estates, but Sarah didn't do this either. When Sarah died in 1737 her husband, Theodore snr, was supposed to deal with Sarah's estate and by extension, Elizabeth Acland's and John Vincent's estates as well. Theodore failed to adminster these estates before he died in 1743 and it was left to his son, Vincent Darley to resolve this legal hiatus, which included some fallout from the scandal of the South Sea Bubble.

The Acland family were caught up in the investment frenzy through one of the company's sub-governors, Peter Burrell, who had married Anne Acland. It is likely that Sarah's husband, Theodore Darley snr, was also an investor and like most other subscribers, lost large amounts of money. Attempts by investors to recoup their losses rumbled on for years after the crash. 1743 - Theodore Darley senior's Will. Theodore wrote his will on 27 August 1743 and died two weeks later. His estate was not inconsiderable. It included Battens, tenements in Lake and Gospelhead, livestock, mortgages, money and personal effects. His two sons clashed over the will's contents. Vincent, being the eldest son received the bulk of the estate. Theodore junior, the second and youngest son, received one shilling. Theodore contested the will but in 1744 the court decided that he he had no justifiable claim and probate was granted to Vincent. Resentment would have festered between the two brothers. 1759 - Vincent Darley's Will. Vincent wrote his will in 1759. He had had no children and was determined to ensure that his siblings, other than his sister Essex, did not significantly benefit from his death. The most important bequests were arranged in this order in the will:

A problem that worried Vincent was that some of the real estate, including Battens, was owned but had a restriction on it. The restriction controlled who the future owners were to be, and defined them in law. This was not unusual with property at the time as families often passed property down over many generations. George Vincent Langworthy and Elizabeth Darley were not cited as the future owners, either by name or family relationship, on the title documents for the real estate. In September 1763 Vincent decided to do something about this through a legal process called 'Common Recovery', which would remove the restriction. 1763 - Common Recovery. This was a long established legal collusion. By using this process Vincent knowingly conveyed the restricted property as an unrestricted property to a third party, and then recovered it as an unrestricted property, thereby losing the restriction. Vincent seems to have been unaware, though, that the law dictated that losing control of the property would change the nature of the property, thereby revoking those parts of his will that mentioned it. It was as if the now unrestricted, recovered real estate had not been mentioned in the will and for that part of his estate Vincent would die intestate. Any property not formally bequeathed automatically passed to the "heir at law", which was his brother, Theodore. As Vincent's intention was that the property did not pass to Theodore, Vincent needed to write a new will that revoked his 1759 will and set out his wishes again. Vincent did not rewrite his will.

1764 (February) - Vincent Darley Died. Following Vincent's death came the reading of the will. Theodore, being a practicing lawyer, realized that he was heir at law for the real estate that had had restrictions removed and lodged his intention to contest the will. The dispute worsened as the family wrestled to take possession of the lands, properties, livestock and household goods. 1765 - Theodore Contests The Will In Chancery. Theodore applied to the Court of Chancery in 1765 asking for all Vincent's real estate to be given to him, along with any income derived from it since Vincent's death. He cited the matter of the common recovery and that no further will had been written. Elizabeth, on her own behalf and that of other beneficiaries from the will, responded admitting that some of Theodore's claim was true. This was the beginning of a process reminiscent of Jarndyce and Jarndyce from Dickens' Bleak House but in this case the adversaries were Vincent's wife, Elizabeth, and her brother in law, Theodore. 1766 (December) - The Case Heard In Chancery. In December 1766 the court heard the case and agreed that Theodore was the heir at law but that the matter of whether or not Vincent's will had been revoked by the common recovery needed to be considered by The Court of Common Pleas. They referred the case for consideration. 1767 (July) - The Court of Common Pleas. The court sat to consider this question in July 1767 and decided that the common recovery did amount to revoking those parts of the will where the common recovery had been applied. The matter was referred to the House of Lords who concurred with this ruling. The case was sent back to Chancery. 1767 (November) - The Case Is Back In Chancery. The case was heard again in November 1767 and Chancery subsequently declared that, based upon the ruling from the Court of Common Pleas, Theodore was entitled under law to the property in question, along with any lost income since Vincent's death, which Elizabeth was now ordered to pay.

"I am intitled unto a ... Tenement called Bondswalls lying Contiguous and adjoyning with Battens aforesaid for the Remainder of a Term of nine hundred years ... It is my Will that the same may goe unto and always ... be enjoyed by the Owner and Possessor of Battens ... and not be separated therefrom ..." (Extract from the tithe map has been reproduced with the kind permission of Kresen Kernow ref: AD1409/1)Considering this, his Lordship, in his ruling, ordered that because Vincent had expressed his wish that whoever owned Battens must also own Bond's Walls, then Bonds Wall's must also be turned over to Theodore. Turning to Vincent's clothes, furniture, cash in hand, livestock, vehicles etc., all held at Battens, the court ruled that because Battens was part of the revocation, so was everything in it. The official report of the case, in a masterful case of understatement, says "The appellant [Elizabeth] being dissatisfied with this decree ... petitioned for a rehearing..." in respect of the personal estate, the chattel estate and Bond's Walls. Elizabeth had become reconciled to losing the real estate but to take everything else was beyond the pale. Soon after this ruling she lodged an appeal. 1769 (April) - Elizabeth's Appeal. Elizabeth lost her case as "... his Lordship was pleased to affirm the former decree", but undaunted she appealed again. 1774 (June) - Elizabeth's Final Appeal Is Heard. This time it was to appeal against the ruling that Bond's Walls should be included in the revocation and, consequently, that the personal and chattel estate ruling should also be overturned. The court considered the difference between Vincent's declared intent and his presumed intent when he wrote his will. It was clear to the court that Vincent intended to give both Battens and Bond's Walls to his wife as an entire and whole gift but he revoked the gift of Battens through the common recovery. This effectively separated the two and whilst Battens was to descend to Theodore, Bond's Walls was still subject to the terms of the will and would go to Elizabeth. The court record says (the italics are taken directly from the court record and were a means for the court to emphasise their understanding and ruling) that whilst Vincent ... " ... declared, that his wife should have and enjoy for her life, the use of all the household goods, plate and furniture at Battens , and the stock [animals] ... [Vincent] did not appear to prescribe that she should enjoy them at Battens .. and that she should not enjoy them elsewhere." ... drawing the distinction between a description of the location of the goods as opposed to a requirement of where the goods were to be enjoyed. 1774 (June) - Final Ruling.The court heard lengthy arguments from both sides and eventually reversed the ruling that granted Bond's Walls, the furniture, household goods and stock to Theodore. Elizabeth was also discharged from the requirement that she had to live at Battens to enjoy her bequests. Theodore, however, won the day as far as Battens and the other real estate was concerned. No further court actions were fought over this issue between Elizabeth and Theodore. The Aftermath Of The Dispute. Presumably Elizabeth moved out of Battens to Langstone near Coad's Green, probably taking her bequests with her; she wrote her will in 1791 whilst living at Langstone. Theodore eventually took unrestricted control of Battens. Whether he took up residence is uncertain, but does not seem likely. He died in 1776 and is not buried in North Hill, indicating that he stayed in and around London. He may have lived at Bovingdon in Hertfordshire with his son, William, who inherited Theodore's estate The legal wranglings rumbled on though, now between Elizabeth and William. In 1782 William applied to have Elizabeth's annuity of £50, sourced from income from the Battens lands, reduced to £39 13s 1d. The settlement of this issue was resolved with the reduced annuity and also with a firm demarcation of ownership of some property. William had Burgess Meadow, part of Battens, Treswell and the moiety (part ownership) of manor of Rillaton Peverell whilst Elizabeth had the Way Cross Land and the Easter Cross Land, part of Battens, Bligh's tenement, Bond's Walls Mill (now Battens Mill), Lake, Lewarne and a moiety of the manor of Rillaton Peverell. This arrangement sounds rather more amicable than the dealings earlier in the century. Elizabeth died in 1791 and is buried near her husband, Vincent Darley, in St Torney's. William died in 1794 in Lyme Regis in Dorset. The lands and property over which the family had quarrelled for so long were bought up over the next few decades by the Rodd family of Trebartha Hall. The Darley family's eventful association with North Hill had come to an end ... |

Vincent Darley's Ghost / Black DogLocal resident, Carole Saunders, not known at all for flights of fancy but for her practical, level headed approach to life in general, recounted this event:

"This memory remains with me and is still very vivid. I now know, of course, that folk around here do not go about such daily tasks and what I witnessed was far from normal." Who was it that she encountered? Could it have been Vincent Darley?

Perhaps the past experiences of others can answer that question. Read on ... "The Dog Called Darley" (April 1926. Old Cornwall 1:9, pp23-26.) "Battens, now a farmhouse, is in North Hill churchtown. It passed from the Battins to the Vincents by marriage, and between 1606 and 1664, also by marriage, from the Vincents to the Darleys, once of Darley in Linkinhorne1, famous for the Darley Oak; the east end of Thomas Vincent's altar tomb (1601) is occupied by the carving of an oak-tree, as if the time were foreseen when Darleys would swallow up Vincents in marriage. The outcome of this latter marriage was Vincent Darley late of Battens in this Parish Esq., who died on the 8th day of February 1764, aged 64 - and is the black dog in question.

"Some years ago a former tenant of Darley Farm, another man, and a boy, went down to the Ford and waited, at dead of night, to see what they'd see. Presently they heard the "pit-pat, pit-pat, pit-pat" of padded feet coming towards them, then two great shining eyes appeared, and lastly a big black dog! The boy's hair lifted, the farmer flung back his stick to hit out—and here comes the anti-climax; for the three, having either expected to see "Darley" in his own shape, or else having taken comfort from the very real howl of the hit dog, went back home unhurried and in peace, and said nothing more about ghosts. Yet the fact remains, they set out expecting to see something not of this world. And that something was "Darley." "He was seen near "Bodandel" or Botternell Turning by three people; two women, and a man akin to the woman who told me this. They were walking from Darley to Berriow after chapel one Sunday night, when he appeared to them as a black dog, and after the manner of such "dogs," pushed them apart, taking the crown of the road. Their feelings can best be imagined. "According to another woman, the dog leaves the Liskeard road at Botternell, and follows the lane down to Bathpool and up to Lydgate Corner, that much-hated place. He is then known as "Will Darley"2. But that is a modern accretion due to the dread inspired by a man called Will Darley, who frequented North Hill about fifty years ago, and may still be living. The real "Darley" keeps to the Liskeard road as far as Berriow. "He has been seen near Berriow Bridge, in the old carriage-drive belonging to Battens. This entered Bond's Walls Field just above Berriow Bridge, crossed the road leading from "Isaac's Turning" to North Hill churchtown, went up the steep opposite field, and so down into Battens yard. Two trees are all that now mark the old entrance, "decayed" and "ancient" in 1817, "Darley" is next seen further up the old drive, where it crosses the steep field next to Battens yard. Grace Blatchford4 and two others were going arm-in-arm over the field from Battens yard to Bond's Walls on their way to Berriow, and they were forced to unlink arms for him to pass. Grace told my informant. It is about seventy years since this happened. "And finally "Darley" is seen at Battens. A certain woman was weeding in the garden at Battens, when her heart nearly stopped beating, and she looked up, and there stood "Darley." He was in the shape of a man wearing a beaver hat and leggings, with a log of wood on his back. "One hundred and sixty-five years they cover between them—the woman who saw him standing there and who told Grace Lark5; Grace Lark herself, and the woman who was told by Grace Lark, and told me. For "Vincent Darley late of Battens in this Parish Esq." say his wall tablet in the church, died on the 8th day of February, 1764. And the woman who "saw" him had known him alive. She said he was tall; a fine figure of a man, but eccentric and given to wandering. She said this to Grace Lark, who told the woman who told me; so the personality of "Darley" has been preserved for one hundred and sixty five years only by word of mouth. More than happens to most of us. "Since Darley's days Battens, very much rebuilt, has been let out in tenements, has housed a dame school under Mrs. Rodda6, and for about one hundred years has been let to the Palmers, the family of yeoman farmers now in residence. It has also been very well haunted, as Mrs. Rodda6 could witness: ghost china and ghostly silk have chinked and rustled, and "Darley" has driven his coach like thunder into the yard. One of the Palmers' men had to saddle up very early in the morning to go somewhere—and the coach came! There was the most awful racket—the farmhorses stampeded, and the terrified man thought the house was falling to pieces, though the people inside heard nothing. "There was also — but that again was in Mrs. Rodda's time — the little matter of the string-drawn trolley which was not the coach!" Note: Not all the 'facts' stated in this article can be substantiated or proven but the article has been faithfully reproduced, word for word. Readers can evaluate for themselves the accuracy of any statements contained in the article but must bear in mind, this is a ghost story! Footnotes 1 The connection between the surname and the place name is not proven (see above) 2 William "Will" Darley was born in 1837, one of twins, the first children of John Darley and Elizabeth Pearce. This branch of the family traces its line back through John-Nathan Darley, the son of John Darley and Mary Crocker (see the family tree above). In the 1850s William joined the 58th Regiment of Foot but his service seems to have been short lived as he embarked on a career of burglary and prison sentences. In 1870 he was sentenced, for a burglary in Tavistock, to seven years in prison, followed by four years police supervision after his release. Having been released in 1877 he immediately absconded and The Police Gazette published his description, seeking his detention. By 1881 he was in Portland Prison in Dorset; this was probably a second term of seven years for burglary. In 1884 he was convicted again for housebreaking and his two terms of seven years were taken into consideration when he was then sentenced to ten years penal servitude. In 1891 he was in Aylesbury Prison in Buckinghamshire. His fate after that is uncertain but he may have been buried in Tower Hamlets, London in February of 1901. He never married and had children, as far as is known, but the census return for 1881 shows him as married. 3 "Catern" was Catherine Buckingham (nee Lark) (1789-1875), the wife of Richard Buckingham (1789-1860). 4 Grace Blatchford (1815-1893). 5 Grace Lark (nee Buckingham) (1812-1881), the wife of John Lark (c1810-1897); Grace was the first cousin once removed of Richard Buckingham who married Catherine Lark (see footnote 3). 6 This may have been Mrs Rodd, wife of the Rector. No family of Rodda has been identified in the parish at this time. |

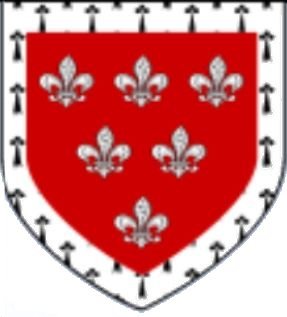

The headline image shows Reverend John-Nathan Darley (c1620-1699), the Darley Coat of Arms, St Torney's Church as it was in the 17th century and Reverend John Darley (1648-1708) |

A devout Christian, and of Puritan leanings, he met

A devout Christian, and of Puritan leanings, he met  From 1613 to 1618 Daniel Featley was Rector of St Torney's in North Hill. He was invited to take up the prestigious living of St Mary's, Lambeth, which he naturaly accepted, leaving a vacancy in North Hill. In Lambeth Daniel was in almost daily conversation with the Archbishop of Canterbury whose palace adjoined St Mary's (as shown here). It would be no surprise to learn that some influence was brought to bear to ensure that Daniel's brother in law, John Darley, was granted the position of Rector of St Torney's.

From 1613 to 1618 Daniel Featley was Rector of St Torney's in North Hill. He was invited to take up the prestigious living of St Mary's, Lambeth, which he naturaly accepted, leaving a vacancy in North Hill. In Lambeth Daniel was in almost daily conversation with the Archbishop of Canterbury whose palace adjoined St Mary's (as shown here). It would be no surprise to learn that some influence was brought to bear to ensure that Daniel's brother in law, John Darley, was granted the position of Rector of St Torney's.

Whilst his father was the squire of Battens, Vincent was an attorney at law based in Callington. In 1735 he took on a young articled clerk, John Browne, to learn the ways of the legal system. After his father's death he returned to Battens as squire. In 1758 Vincent led a case against John Luskey, a local farmer. Vincent and his neighbouring farmers with rights to graze animals on Twelve Men’s Moor, objected to John Luskey's excessive over-grazing of the moor. You can read more about this through the links on the

Whilst his father was the squire of Battens, Vincent was an attorney at law based in Callington. In 1735 he took on a young articled clerk, John Browne, to learn the ways of the legal system. After his father's death he returned to Battens as squire. In 1758 Vincent led a case against John Luskey, a local farmer. Vincent and his neighbouring farmers with rights to graze animals on Twelve Men’s Moor, objected to John Luskey's excessive over-grazing of the moor. You can read more about this through the links on the

"I moved into Botternell Farm in February 2008 and it was while I was travelling from home, along the B3254 towards Liskeard, I slowed down to pass an old man dressed in dark clothing, hunched over and carrying a bundle of kindling on his right shoulder. This encounter was just past North Darley House on the left hand side of the road. I was so intrigued by the image that I remarked to my husband on my return home about how 'quaint' life is in rural Cornwall and described what I had seen. At this time I had no knowledge of any ghost stories and in fact did not learn about Darley's Ghost until several years later.

"I moved into Botternell Farm in February 2008 and it was while I was travelling from home, along the B3254 towards Liskeard, I slowed down to pass an old man dressed in dark clothing, hunched over and carrying a bundle of kindling on his right shoulder. This encounter was just past North Darley House on the left hand side of the road. I was so intrigued by the image that I remarked to my husband on my return home about how 'quaint' life is in rural Cornwall and described what I had seen. At this time I had no knowledge of any ghost stories and in fact did not learn about Darley's Ghost until several years later. "Darley" has a regular route, and has been seen on all parts of it, either as a black dog or as a man carrying a bundle of sticks on his back; but mostly as the dog. He is known for some miles round. His route begins at Darley Ford, although by 1588 at the latest, the Darleys had left "Derley", and it ends at Battens.

"Darley" has a regular route, and has been seen on all parts of it, either as a black dog or as a man carrying a bundle of sticks on his back; but mostly as the dog. He is known for some miles round. His route begins at Darley Ford, although by 1588 at the latest, the Darleys had left "Derley", and it ends at Battens. and Catern

and Catern