|

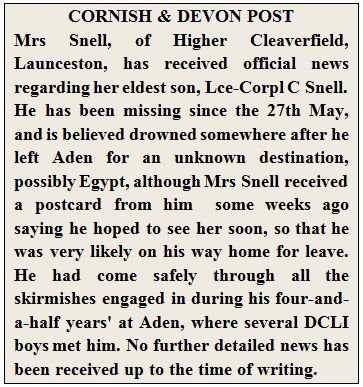

Claude's mother was Mary Ann Snell (nee Stephens) and she had had lived almost all of her early life in Bathpool. She was the daughter of the village blacksmith and she married a Royal Navy sailor in Plymouth in 1882. They set up home in Bathpool. Later, her husband George left the navy with a pension and became the village postman. They had six children, all born in Bathpool, two daughters (Clara and Sarah) and four sons (Claude, George, Richard and Henry). Claude was baptized in St Torney's Church on 15th Jun 1884. In 1908 Mary's life changed when her husband died and his Royal Navy pension ceased. She moved into North Hill village and from there she moved to St Stephen's in Launceston.

As a youth Claude was an apprentice millwright but he had chosen a career with the Royal Engineers, having enlisted in July 1905, a few days after his 21st birthday. This normally meant that he would do three years' actual soldiering before being transferred to the reserve for nine years. Instead he chose to do the full twelve years' service in the regular army. In the 1911 census he is recorded as an electrician whilst serving as a sapper with the Royal Engineers on Gibraltar. He was later attached to 'H' company of the Bombay Defence Light Section in May 1915. In 1918 he was on board the troop ship Leasowe Castle en route for Marseilles from Alexandria in Egypt. As a youth Claude was an apprentice millwright but he had chosen a career with the Royal Engineers, having enlisted in July 1905, a few days after his 21st birthday. This normally meant that he would do three years' actual soldiering before being transferred to the reserve for nine years. Instead he chose to do the full twelve years' service in the regular army. In the 1911 census he is recorded as an electrician whilst serving as a sapper with the Royal Engineers on Gibraltar. He was later attached to 'H' company of the Bombay Defence Light Section in May 1915. In 1918 he was on board the troop ship Leasowe Castle en route for Marseilles from Alexandria in Egypt.

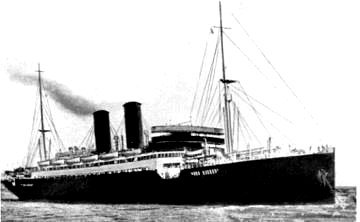

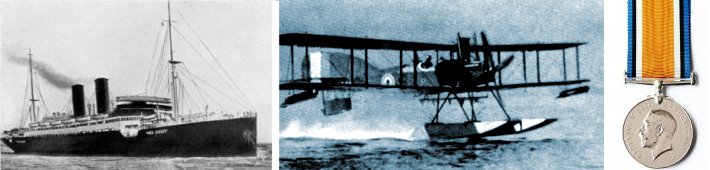

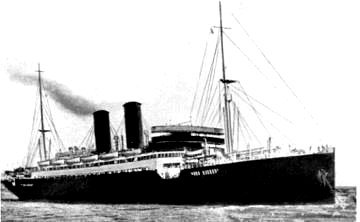

The Union Castle steamship HMT Leasowe Castle was employed as a hospital and troopship from 1917 onwards. On 20th April 1918, while operating as a hospital ship, she was torpedoed off Gibraltar by the German U-boat U35 but managed to reach port for repairs. The Union Castle steamship HMT Leasowe Castle was employed as a hospital and troopship from 1917 onwards. On 20th April 1918, while operating as a hospital ship, she was torpedoed off Gibraltar by the German U-boat U35 but managed to reach port for repairs.

Less than six weeks since her last encounter with a German torpedo, on 27th May 1918 with Claude on board, the Leasowe castle was again torpedoed, this time by UB51, commanded by Kapitanleutnant Ernst Krafft. This resulted in her sinking off the North African coast, 100 miles west of Alexandria. 92 men were lost including Claude Snell. The ship was carrying 2,900 troops at the time.

Claude's name is recorded on the Chatby Memorial in Alexandria as well as the North Hill and Launceston War Memorials. Claude's name is recorded on the Chatby Memorial in Alexandria as well as the North Hill and Launceston War Memorials.

|

The story of the last few days of HMT Leasowe Castle and the experiences of the members of Claude's battalion can be followed here:

|

|

23rd May

At 0915hrs the Battalion paraded at Sidi Bisr Camp near Alexandria for the last time and marched to Victoria Station, entraining there at 1100 a.m. In the train along with them were 543 other ranks of the Warwickshire & South Nottinghamshire Yeomanry Machine Gun Battalion.

The train arrived at the docks at about noon, and embarkation on H.M.Transport Leasowe Castle was commenced following the embarkation of the Warwickshire & South Nottinghamshire Yeomanry detachment. There was only one gangway and embarkation of the men was complete by 1530hrs, and baggage was stowed in the hold by 1630. Embarkation strength of the Battalion was 51 officers and 984 other ranks.

The Leasowe Castle was a 10,000 ton ship which, having been built in England for a Greek company, was requisitioned by the Admiralty and handed over to the Union Castle Company. Commanded by Captain Holl, she had eight troop decks and carried 42 boats.

Also on board along with Warwickshire and South Notts Yeomanry Battalion of machine gunners were another company of Machine Gun Corps and a few attached officers and details. On completion of embarkation the ship was taken out in to the middle of the harbour where it anchored.

|

25th May

On board ship all day, still in harbour.

|

26th May

At anchor; remaining until 5.00pm, when SS Leasowe Castle cast off and proceeded in company with five other troopships convoyed by Japanese destroyers, and other vessels such as trawlers and even a captive kite balloon for observation. Several sea-planes accompanied the convoy for some distance. The balloon was towed aloft until dark when it was hauled down.

The convoy steamed in line ahead until it came to the end of the swept channel and then came in to "T" formation, with the Leasowe Castle 3rd in the leading line. Every precaution was taken to prevent light showing after dark, and as many men as possible were ordered to sleep on deck at their emergency station

The Battalion was duty Battalion this day and found all the guards until 1600 when it was relieved by the Warwickshire and S Notts Battalion. |

27th May

It was a brilliant moonlight evening, with a calm sea, and from the decks every ship in the convoy and it's protective ring of trawlers and destroyers could be seen An obvious target for any submarines in the area.

All had gone well, but at 0025hrs, about 100 miles from Alexandria, the Leasowe Castle was hit by a torpedo on the starboard side a little forward of amidships, under the after funnel. The engines were stopped practically at once and she remained on an even keel, settling slightly by the stern.

Troops paraded and fell in at their emergency stations immediately. Rolls were called. Men berthed in the lower decks had been encouraged to sleep on deck and as near as their emergency stations as far as was possible, and this was in practice on this night to roughly half to 80% of company strengths of our Battalion. The amount of movement was thus reduced and there was no confusion.

The order was given by the master of the ship to lower the boats and this was done. Rafts were also flung overboard by the crew assisted by troops on board, largely from the Battalion.

Meanwhile, the remainder of the convoy had disappeared, leaving the Japanese destroyer Katsura and HM Sloop Lily to render assistance.

As soon as the first batch of boats was on the water they were ordered to be filled while the remainder were being lowered; troops were going over the side down ropes and ladders. Boats were ordered by the master to pull over to the sloop and destroyer, discharge troops and pull back to the ship. This order was carried out by some boats but not by all; some boats were left empty and drifting.

The total number of troops on board including officers amounted to 2903. After all the boats had been filled and left the ship, about 0130hrs, there were still roughly 800 to 1000 men left on board. These were mostly troops stationed in the forecastle and on the starboard side. Those on the starboard side had not managed to get away because some of the boats hanging outboard had beeng smashed by columns of water from the explosion. The remainder of those on board were taken off partly by the boats which came back after discharging and partly by the sloop Lily which came along side the forecastle of the Leasowe Castle and made fast with ropes up to within a few seconds of the final plunge. Many men jumped in to the sea during the last few moments and were picked up from rafts, amongst those being the Battalion commander Major Sir St J Gore Bt.

At 0150hrs the Battalion adjutant Captain CH Bennett M.C. reported to the commanding officer, Major Sir St J Gore Bt on the ship's bridge, that all the Battalion were, as far as could be seen, off the ship. The C.O. ordered him to go himself, and he was never seen again.

The ship sank stern first suddenly at 0200 having roughly about 150 men on board nearly all on the forecastle. The following are two eye witness reports of the sinking.Captain Sutton described his experience; this account was written 2 days afterwards.

"We had got about 9 hours out. Nearly all of us were asleep in bed. I was subconsciously aware of a sudden jar, but what I do remember was sitting on my berth and asking what happened, and was told if I didn't get out pretty quickly I should pretty soon know what it was. I pulled on a pair of shoes and tying on my lifebelt scuttled along the corridor, and slipped up at the foot of the stairs. I went straight to our emergency station and found the other men arriving.

They were awfully good on the ship, and there was no panic. The yeoman is a downright good fellow and I take off my hat to him. The ship soon stopped. There was a very slight list. The boats were got off and the rafts too and when all the men were off the ship and I said to about half a dozen still there 'Well we'll go now'.

The water was then awash in the after well deck. So clad in pyjamas, canvas shoes and a wrist watch, I climbed down about six feet of ladder, held my breath, looked at the black water, and dropped quietly in. I had a swim of about 30 to 50 yards. I had a life belt on, a splendid thing. When we got to the life raft (a collapsible canvas sided boat), we rowed and rowed round in circles till a motor launch came and took us in tow, and then we arrived in an auxiliary ship of war. While we were getting on board the auxiliary had 2 torpedoes launched at her but both were misses thank God. A few minutes after, the ship went down with a rush. We made off back towards Alexandria with over 1,100 survivors on board. The night was wonderfully warm and I never felt cold, even in wet pyjamas. However some kind naval officer fitted me out in a naval tunic and a pair of trousers, and of course I was the butt of many jests. All were fitted up with blankets or something to keep the warm and some food. About ten hours afterwards we arrived back in Alex. On the quay we were given clothes, army issue, and the red cross gave us tea and biscuits."

|

| Seventy years later, one of the survivors, Fred Marshall, described his experience: |

"We were on transports going to Marseilles. Six transports and about two cruisers, seven destroyers and a couple of sloops named the Lily and the Ladybird. When we were torpedoed it was just midnight. The officer in charge of us on board came round to ask for volunteers to lower the rafts after the crew had got the lifeboats down. Then, once finished, he stepped up to me and my mate: 'Come on boys, the decks are awash, every man for himself'.

So we scrambled over the side and the ship stood up. The deck was above water. We had life jackets on which was just as well since I couldn't swim very well. It was sixteen minutes past one when my watch stopped; of course they wouldn't go in those days, they weren't waterproof. I swam about out there, and we were anxious that we couldn't get as far as we would want because of the suction of the ship [when it went down]. The crew consisted of a load of Lascars who took the life boats to the rescue ships, the Lily and Ladybird and others. When they got there they got onto the ships themselves [and then] they let the lifeboats go.

It was one of these which I swam out to. We just wore shorts. The sergeants and the sergeant majors, they kept their breeches, as did the officers. Up came somebody in the dark beside of me, my Sergeant Major Legg. We went to clamber up into the boat together, and he said to me, 'Let go of me you bloody fool, I can't get up there with you hanging on to my breeches'. So when we eventually rolled into the boat, I was free, minus one sock and one shoe. He had his breeches full of two or three gallons of water which had held him down from getting in the boat. That made me laugh, did that.

Having got into the boat there was only one oar left. About five or six other fellows gathered together and got into the boat, and we tried to get away with only one oar. As she was going down we tried to get the boat 50 yards from her so she wouldn't suck us down. Eventually around came this motor-boat with two sailors in who chucked us a line and towed us to where we got on the Ladybird. ... There was so many of us on this little sloop that the captain of the ship asked us to get more equally spread all over the ship to keep her balanced." |

|

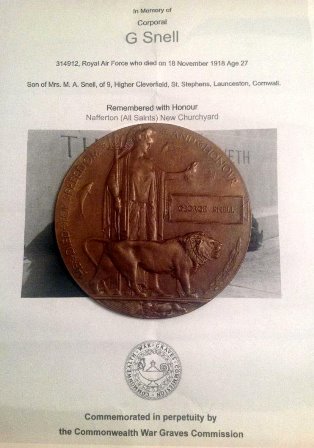

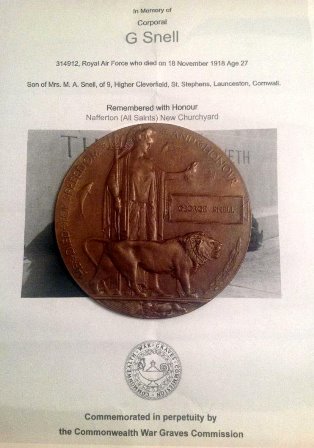

The images of the plaques commemorating the lives of Claude and George Snell have been reproduced here with the kind permission of the current custodian, Kevin Bennett.

Click for a larger image.

|

GEORGE SNELL (1891-1918)

GEORGE SNELL (1891-1918)

|

Corporal George Snell 314912 of the Royal Air Force died from influenza and double pneumonia at The Wold House Hospital in Nafferton, Yorkshire on the 18th November 1918, one week after the armistice was declared. |

|

George was born in 1891 and was two days short of his sixteenth birthday when he entered the Royal Navy as a boy on 13th May 1907. His twelve year service period as a man started when he was eighteen in 1909.

His early naval career saw him serving on ships in home waters as well as in the Caribbean, the Mediterranean and around the East Indies. At the outbreak of World War One he was serving on HMS London, part of the 5th Battle Squadron which was assigned to the Channel Fleet and based at Portland. Their first task was to escort the British Expeditionary Force across the English Channel. The squadron transferred to Sheerness on 14th November 1914 to guard against a possible German invasion. It was whilst here that George was promoted to leading seaman.

On 19th March 1915, HMS London was transferred for service in the Dardanelles Campaign. She joined the squadron at Lemnos on 23rd March 1915, and supported the main landings at Gaba Tepe and Anzac Cove on 25th April 1915. The London, along with battleships HMS Implacable, HMS Queen, and HMS Prince of Wales, was transferred to the 2nd Detached Squadron which had been organised to reinforce the Italian Navy in the Adriatic Sea when Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary. She was based at Taranto, Italy and underwent a refit at Gibraltar in October 1915 during her Adriatic service. In October 1916, the London returned to the United Kingdom and was paid off at Devonport Dockyard.

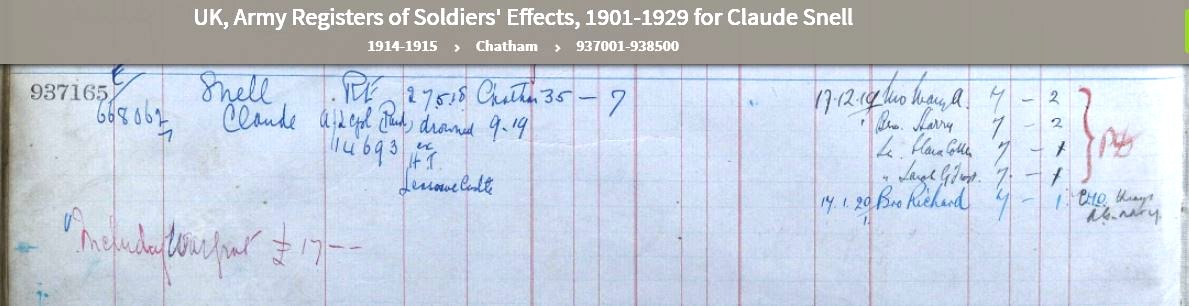

After two months based at HMS Vivid, a shore establishment, George was transferred to the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS), HMS Daedalus at Lee-on-Solent. Naval aviation began in 1917 when the RNAS opened the Naval Seaplane Training School. Initially, the aircraft (Short 184 Seaplanes as shown in the banner at the top of this page) had to be transported from their temporary hangars to the top of the nearby cliff and then lowered by crane onto a trolley which ran on rails into the sea. After two months based at HMS Vivid, a shore establishment, George was transferred to the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS), HMS Daedalus at Lee-on-Solent. Naval aviation began in 1917 when the RNAS opened the Naval Seaplane Training School. Initially, the aircraft (Short 184 Seaplanes as shown in the banner at the top of this page) had to be transported from their temporary hangars to the top of the nearby cliff and then lowered by crane onto a trolley which ran on rails into the sea.

On 12th March 1917 George was posted to RNAS Howden (shown here) which was an airship station fifteen miles south east of York. It was opened in March 1916 to cover the east coast ports' shipping from attacks by German U-boats, but Howden-based airships never engaged in direct combat. The base and its complement transferred to the Royal Air Force when it was established on 1st April 1918. On 12th March 1917 George was posted to RNAS Howden (shown here) which was an airship station fifteen miles south east of York. It was opened in March 1916 to cover the east coast ports' shipping from attacks by German U-boats, but Howden-based airships never engaged in direct combat. The base and its complement transferred to the Royal Air Force when it was established on 1st April 1918.

After almost a year at Howden George transferred again, this time to the East Fortune airship base, 25 miles east of Edinburgh. This airship base had a mooring station 60 miles south at Chathill in Northumberland, and this proved to be George's final posting. He was here as Corporal George Snell 314912 of the RAF and was employed as a rigger. Throughout his career with the Royal Navy, the RNAS and the RAF, his conduct was always recorded as 'Very Good'.

George's final days were spent at Wold House (shown here), an auxiliary Red Cross Hospital near Driffield in Yorkshire. Auxiliary hospitals were attached to Central Military Hospitals, which looked after patients who remained under military control. The convalescent patients at these hospitals were generally less ill or less seriously wounded than those at other hospitals. Servicemen preferred the auxiliary hospitals to military hospitals because they were not so strict, less crowded and more homely. George's final days were spent at Wold House (shown here), an auxiliary Red Cross Hospital near Driffield in Yorkshire. Auxiliary hospitals were attached to Central Military Hospitals, which looked after patients who remained under military control. The convalescent patients at these hospitals were generally less ill or less seriously wounded than those at other hospitals. Servicemen preferred the auxiliary hospitals to military hospitals because they were not so strict, less crowded and more homely.

George died from influenza and double pneumonia on 18th November 1918, one week after the armistice was declared. He was buried in the local Nafferton All Saints New Churchyard. His name is inscribed on the war memorials in North Hill and in Launceston.

|

|

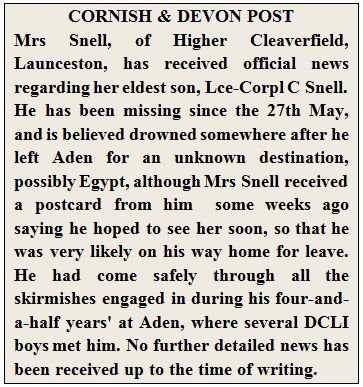

The images at the top of the page show (L-R): HMT Leasowe Castle; a Short 184 Seaplane; British War Medal (WW1).

|

|

|

CLAUDE SNELL (1884-1918)

CLAUDE SNELL (1884-1918) As a youth Claude was an apprentice millwright but he had chosen a career with the Royal Engineers, having enlisted in July 1905, a few days after his 21st birthday. This normally meant that he would do three years' actual soldiering before being transferred to the reserve for nine years. Instead he chose to do the full twelve years' service in the regular army. In the 1911 census he is recorded as an electrician whilst serving as a sapper with the Royal Engineers on Gibraltar. He was later attached to 'H' company of the Bombay Defence Light Section in May 1915. In 1918 he was on board the troop ship Leasowe Castle en route for Marseilles from Alexandria in Egypt.

As a youth Claude was an apprentice millwright but he had chosen a career with the Royal Engineers, having enlisted in July 1905, a few days after his 21st birthday. This normally meant that he would do three years' actual soldiering before being transferred to the reserve for nine years. Instead he chose to do the full twelve years' service in the regular army. In the 1911 census he is recorded as an electrician whilst serving as a sapper with the Royal Engineers on Gibraltar. He was later attached to 'H' company of the Bombay Defence Light Section in May 1915. In 1918 he was on board the troop ship Leasowe Castle en route for Marseilles from Alexandria in Egypt.  The Union Castle steamship HMT Leasowe Castle was employed as a hospital and troopship from 1917 onwards. On 20th April 1918, while operating as a hospital ship, she was torpedoed off Gibraltar by the German U-boat U35 but managed to reach port for repairs.

The Union Castle steamship HMT Leasowe Castle was employed as a hospital and troopship from 1917 onwards. On 20th April 1918, while operating as a hospital ship, she was torpedoed off Gibraltar by the German U-boat U35 but managed to reach port for repairs. Claude's name is recorded on the Chatby Memorial in Alexandria as well as the North Hill and Launceston War Memorials.

Claude's name is recorded on the Chatby Memorial in Alexandria as well as the North Hill and Launceston War Memorials.

After two months based at HMS Vivid, a shore establishment, George was transferred to the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS), HMS Daedalus at Lee-on-Solent. Naval aviation began in 1917 when the RNAS opened the Naval Seaplane Training School. Initially, the aircraft (Short 184 Seaplanes as shown in the banner at the top of this page) had to be transported from their temporary hangars to the top of the nearby cliff and then lowered by crane onto a trolley which ran on rails into the sea.

After two months based at HMS Vivid, a shore establishment, George was transferred to the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS), HMS Daedalus at Lee-on-Solent. Naval aviation began in 1917 when the RNAS opened the Naval Seaplane Training School. Initially, the aircraft (Short 184 Seaplanes as shown in the banner at the top of this page) had to be transported from their temporary hangars to the top of the nearby cliff and then lowered by crane onto a trolley which ran on rails into the sea. On 12th March 1917 George was posted to RNAS Howden (shown here) which was an airship station fifteen miles south east of York. It was opened in March 1916 to cover the east coast ports' shipping from attacks by German U-boats, but Howden-based airships never engaged in direct combat. The base and its complement transferred to the Royal Air Force when it was established on 1st April 1918.

On 12th March 1917 George was posted to RNAS Howden (shown here) which was an airship station fifteen miles south east of York. It was opened in March 1916 to cover the east coast ports' shipping from attacks by German U-boats, but Howden-based airships never engaged in direct combat. The base and its complement transferred to the Royal Air Force when it was established on 1st April 1918. George's final days were spent at Wold House (shown here), an auxiliary Red Cross Hospital near Driffield in Yorkshire. Auxiliary hospitals were attached to Central Military Hospitals, which looked after patients who remained under military control. The convalescent patients at these hospitals were generally less ill or less seriously wounded than those at other hospitals. Servicemen preferred the auxiliary hospitals to military hospitals because they were not so strict, less crowded and more homely.

George's final days were spent at Wold House (shown here), an auxiliary Red Cross Hospital near Driffield in Yorkshire. Auxiliary hospitals were attached to Central Military Hospitals, which looked after patients who remained under military control. The convalescent patients at these hospitals were generally less ill or less seriously wounded than those at other hospitals. Servicemen preferred the auxiliary hospitals to military hospitals because they were not so strict, less crowded and more homely.