|

||

| The Landrey Or The Maurice Family? |

Private William Werry Landrey 92871 11th Battalion Royal Tank Corps was killed in action at the Battle of The Scarpe, near Arras in France, on 26th August 1918.

William Werry Landrey's birth was registered as William Martin Landry (sic) but that this was 'changed' in family usage. His father, Harry (b1868), was the son of Thomas Werry Landry and Emma (nee Martin) and it is very common to use the maiden name of one of the child's grandmothers as a middle name for the child. The ages given in the census returns indicate a birth date between September 1896 and March 1897. De Ruvigny's record of his death gives his birthplace as Harcombe (a large house with grounds just north west of Chudleigh which would need a gamekeeper) and his date of birth as 3 October 1896. They moved to North Hill around 1897 and all the children went to North Hill School.

William's family lived at Lemarne in North Hill. Both his grandfather and his father were gamekeepers to the Rodd family of Trebartha Hall. As a young man, before entering the army, William was a gamekeeper himself. His father, Harry, was still living in Lemarne when Trebartha Hall was demolished in 1949. Harry is mentioned in the newspaper report.

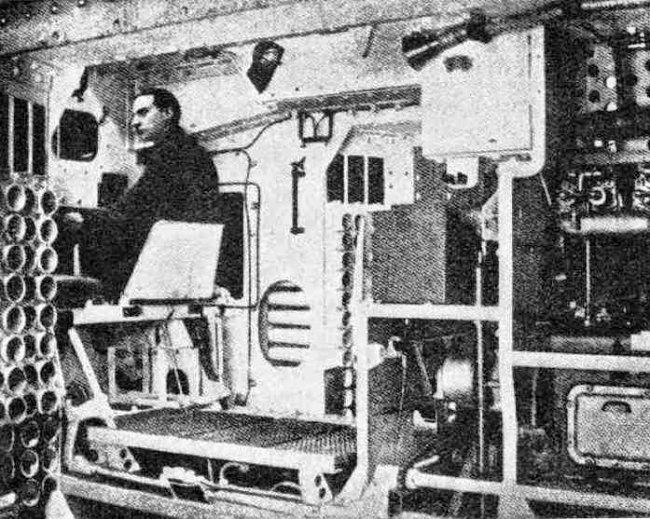

William joined the 1st Royal Devon Yeomanry in May 1915 and was in the Machine Gun Corps. In March 1917 he volunteered for the newly created Tank Corps. He went to France at the end of 1917 and served in the 11th Division as one of the crew in a Mark V tank. The Mark V was introduced into combat in early July 1918 and had a top speed of 5 mph. It had a crew of eight men: a commander, a driver and six gunners. Click on this image to see the poster used at the book launch that features William and the Mark V tank. You can see other posters here. We now know that the image on the poster and in The Fallen of North Hill is not William, which is explained here.

William joined the 1st Royal Devon Yeomanry in May 1915 and was in the Machine Gun Corps. In March 1917 he volunteered for the newly created Tank Corps. He went to France at the end of 1917 and served in the 11th Division as one of the crew in a Mark V tank. The Mark V was introduced into combat in early July 1918 and had a top speed of 5 mph. It had a crew of eight men: a commander, a driver and six gunners. Click on this image to see the poster used at the book launch that features William and the Mark V tank. You can see other posters here. We now know that the image on the poster and in The Fallen of North Hill is not William, which is explained here.

The crew were packed like sardines in conditions where the heat could reach over 120 degrees Fahrenheit. The air was poisoned, not just because the eight man crew were breathing in a confined space, but also by carbon monoxide, fuel and oil vapours from the engine and cordite fumes from the guns. Crew members had been known to lose consciousness while in the tanks, or to become violently sick when exposed to fresh air again. It was not uncommon for crews to be rendered incapable of completing quite short journeys.

Crews wore a variety of headgear including protective leather helmets to minimise impact with the internal superstructure as they bounced around inside the tank, even on smooth terrain. They also wore gas helmets with goggles; in the earlier, thinner-plated tanks, chainmail masks were worn to ward off 'splash' from melted splinters, rivets and other objects knocked off by any bullets which had penetrated the tank. It was also difficult to communicate within the tank and to units outside. The tank officer often had to get out and walk, to reconnoitre his path or to work with the infantry. A direct hit by an artillery or mortar shell could cause the fuel tanks to burst open and incinerate the crew. Special salvage companies were needed to reclaim the bodies when this had occurred.

Crews wore a variety of headgear including protective leather helmets to minimise impact with the internal superstructure as they bounced around inside the tank, even on smooth terrain. They also wore gas helmets with goggles; in the earlier, thinner-plated tanks, chainmail masks were worn to ward off 'splash' from melted splinters, rivets and other objects knocked off by any bullets which had penetrated the tank. It was also difficult to communicate within the tank and to units outside. The tank officer often had to get out and walk, to reconnoitre his path or to work with the infantry. A direct hit by an artillery or mortar shell could cause the fuel tanks to burst open and incinerate the crew. Special salvage companies were needed to reclaim the bodies when this had occurred.

On 26th August 1918 William was in one of nine tanks supporting the Canadian Infantry west of Arras in the The Battle of the Scarpe. The orders were to advance from the road connecting Arras and Cambrai, in order to capture Orange Hill, which was an area overlooking the village of Monchy-le-Preux.

On 26th August 1918 William was in one of nine tanks supporting the Canadian Infantry west of Arras in the The Battle of the Scarpe. The orders were to advance from the road connecting Arras and Cambrai, in order to capture Orange Hill, which was an area overlooking the village of Monchy-le-Preux.

The Canadians had to overcome strong German defensive positions. The battle was intense and the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions' casualties amounted to 254 officers and 5,547 men from other ranks. Five tanks were knocked out in the action and, as was usual, the crews joined the infantry. By the end of the day they had captured the village and also Wancourt. They had advanced four miles, a significant distance when measured against the territorial gains of most of the earlier battles. It was during this action that William was killed. This attack began pushing the German Army out of their prepared positions and back into open country. For them it was the beginning of the end.

William is buried in Windmill British Cemetery at Monchy-le-Preux and is remembered on the North Hill War Memorial.

De Ruvigny's Roll

Landrey or Maurice?

This photograph is wrongly thought to be of the Landrey family outside their home in Lemarne and was taken around 1910. The location of Lemarne is not in dispute and the people shown in the 1911 census can be deduced from the photograph, but who is the tall gentleman at the back?

Is this the Landrey family or, perhaps, the Maurice family?

There exists an engaging theory as to the identity of the people shown in the photograph.

The photograph has been kindly supplied by Robert Latham. Click on the photograph to see a larger image.

The images at the top of the page show (L-R): William Werry Landrey (depending upon the interpretation of the family photograph); recruitment poster for the CEF; The flag of the Dominion of Canada; British War Medal (WW1), issued to Canadian Forces |

WILLIAM WERRY LANDREY (1897-1916)

WILLIAM WERRY LANDREY (1897-1916)