WILTON |

|

The story of an ordinary Cornish family in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with some genealogical observations on family events. |

|

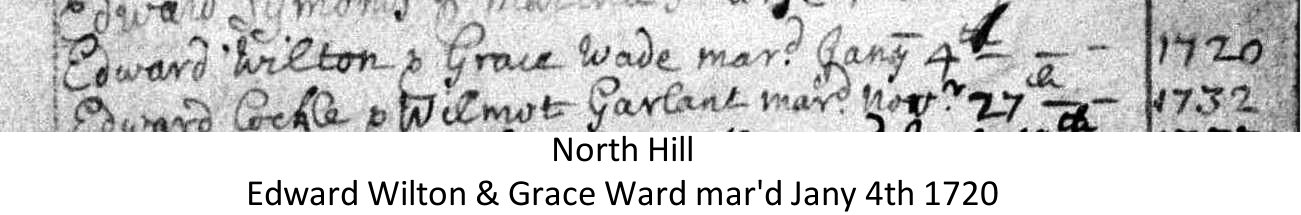

In 1720 Edward Wilton married Grace Ward in St Torney’s in North Hillin Cornwall. Where they were before this date is not definitely known but it is probable that Grace was born in Jacobstowe and that Edward came from St Cleer. |

|

|

|

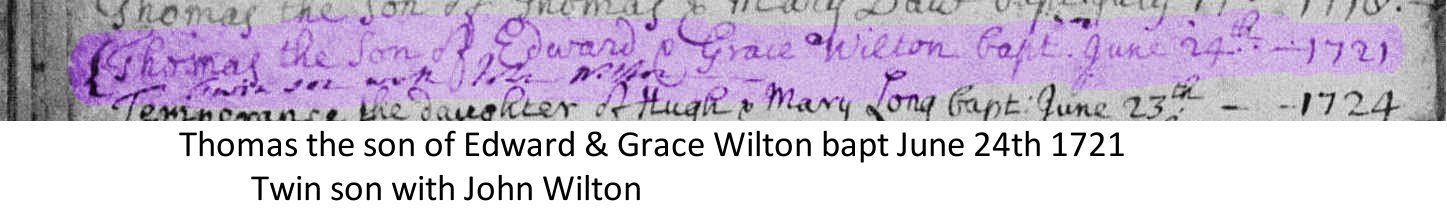

These were the days of the Julian calendar. From 1155 to 1752 when the civil or legal year in England began on 25 March (Lady Day), using modern notation the marriage of Edward and Grace would be dated as the 4th of January 1721. Six months after the wedding the couple were back in St Torney’s for the baptism of their twin boys, John and Thomas, although it would seem that John’s entry was an afterthought. No further children have been identified for Edward and Grace either older or younger than the twins, from the parish registers. |

|

|

|

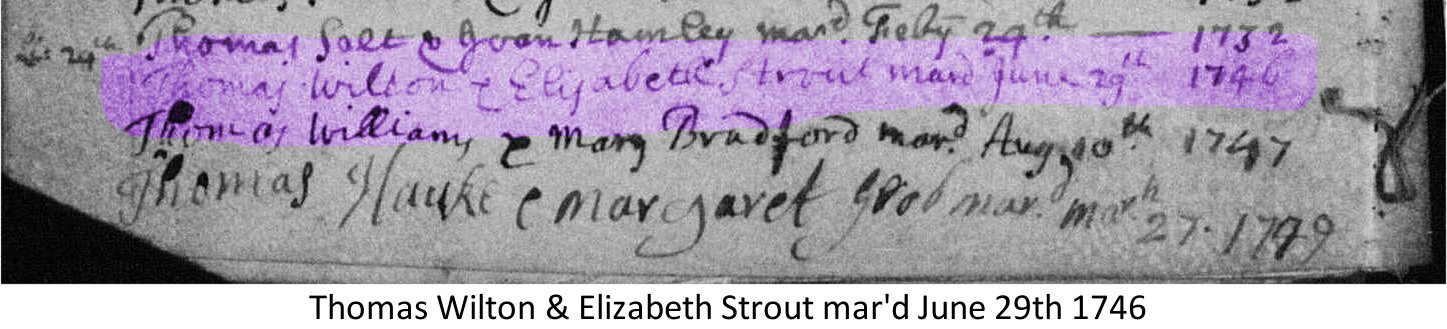

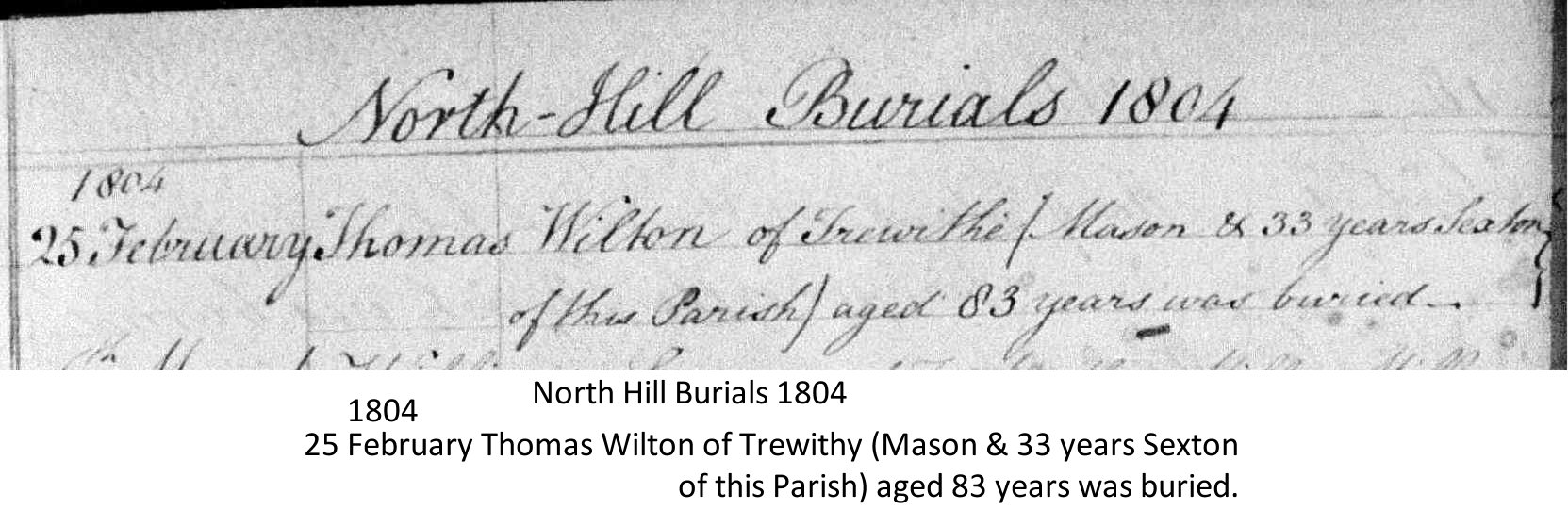

Edward was buried in St Torney’s the day after the 25th anniversary of his marriage to Grace and she followed him into the graveyard eighteen years later in 1764. It is possible to speculate that Edward was somewhat older than Grace from their dates of death and that Grace may not have been a young woman when the twins were born, otherwise they may have had other children. Looking into the lives of the twins, there is no trace of a marriage for John who died a little before his 33rd birthday in 1754. Thomas, however, married in 1746, had nine children and lived to the grand old age of 82. |

|

|

|

His wife, Elizabeth, was not so fortunate, having been buried in St Torney’s in 1787. If she was the Elizabeth Strout that was baptised in South Petherwin in 1723, and this seems likely, then she would have been about 64 years old when she died. From his burial entry we know that Thomas was a mason and for 33 years was sexton in the parish of North Hill. |

|

|

|

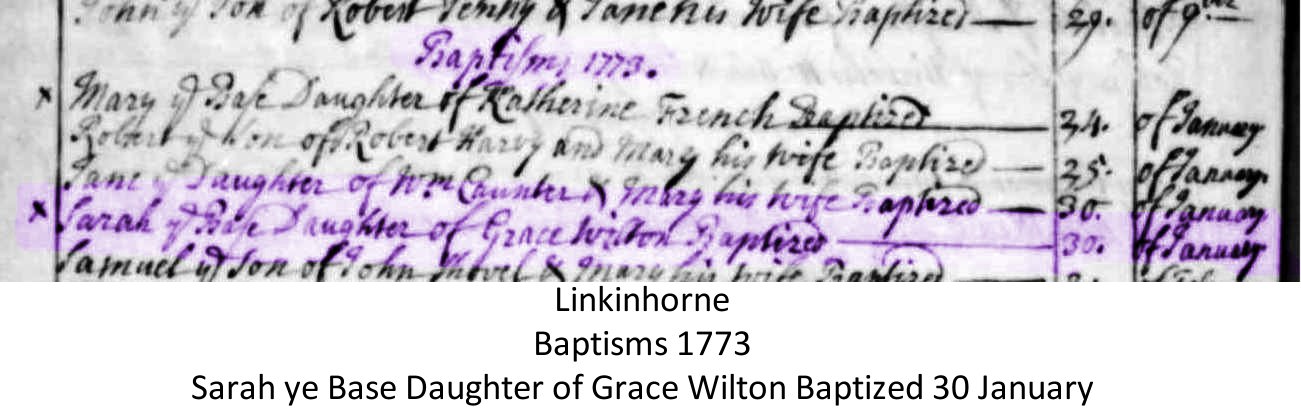

A sexton was an assistant to the Parish Clerk and carried out the more menial duties such as grave digging, bell ringing and other duties around the church and churchyard. This position was often appointed by the church wardens or the incumbent and may have carried a salary although this could just as easily be a payment of a fixed sum for each burial. Of Thomas and Elizabeth’s nine children we know that at least three of them, and possibly as many as five of them, died in early childhood. The eldest of the remaining four was Grace; her story is the more interesting and continues below but ahead of that we can look quickly at her siblings. Elizabeth was the second child and she had a son named John Littlejohn Wilton in 1776; he was born out of wedlock and hence had his mother’s surname until he died, childless, in 1848. It is likely that his middle name of Littlejohn was derived from his biological father’s name but we shall never know for certain if that was true. Elizabeth later married William Sargent, a local husbandman; this occupation is a step up from agricultural labourer but not as high on the social scale as a yeoman or farmer. The derivation of husbandman, meaning ‘master of the house’ can be seen from the first two elements of the word; ‘hus’ is derived from house and ‘band’ from bond indicating an owner of property. No evidence of children has been found for Elizabeth and William. The third child was Edward, born 1751, who lived and worked in Liskeard. He married Sarah Wills, a North Hill girl, in St Torney’s in 1787. Four children followed - Sarah (born 1788), Richard (born 1791 and died as a baby), Ann 1793 and another Richard (born 1797, and who has descendants in South East England alive today). Edward became a widower in 1807 when his wife Sarah died and was buried in North Hill leaving him with two daughters aged 19 and 14, and a 10 year old son. Edward died just six years later and is buried in Liskeard. The youngest child of Thomas and Elizabeth was Thomas, born in 1767. This was the third child they had named Thomas, the other two having died as infants. He married, lived and died in Linkinhorne with his wife Joan (nee Harvey) and son, Edward, who died at the age of 30, unmarried and without offspring. Returning to Grace, the eldest child in the family, she was living in Linkinhorne by the early 1770s. She had a relationship with Jonathan Tabb and he is suspected of being the father of Grace’s daughter, Sarah who was born in 1773. In the Linkinhorne register, Sarah is shown as “the base daughter” of Grace meaning that she was born to an unmarried mother and illegitimate. |

|

|

|

Linkinhorne Church is shown here, the photograph was taken by Roy Reed in 2014; |

Sarah being illegitimate, it may to be expected that both mother and daughter would be stigmatized. The understanding of illegitimacy being a social evil is founded on more recent middle and upper class attitudes and does not necessarily reflect earlier pragmatic thinking, although it is a fact that most religious preachers throughout the ages have encouraged their congregations towards a higher moral standing. The condition of being an unmarried mother was not very unusual, indeed you can see from the extract from the parish register that another “base daughter”, Mary (daughter of Katherine French), was baptized in Linkinhorne less than a week earlier. The stigma, therefore, may only have existed with a small section of this rural, agricultural community. It is interesting to note that the two illegitimate children in the extract have been marked with a cross. Sarah died when she was 20. She had lived at Bearah at the time and her burial entry in the North Hill parish register of 1793 shows that she was the “natural daughter”, another euphemism for illegitimate, of “Grace Wilton (now Budge) by Jonathan Tabb”. This may well have been common knowledge within the community and may also have been correct. It is reasonable to surmise that Grace may have provided the information, but as she could not read and write, perhaps she was oblivious to what was being recorded by the parish clerk or the incumbent. Perhaps the information had been provided by her stepfather, John Budge. We know from what follows below that he was literate but may wish to dissociate himself from a stepdaughter who was born years before he married Grace. This leads us to the marriage of Grace to John Budge, junior, in 1787 in Linkinhorne, shown below. John’s father was named John and lived in Linkinhorne until his death in 1810, hence at this marriage the groom is shown as John Budge junior. This older type of format does not demand to know the marital status of the bride and groom but from other documents we know that John had had a first wife before marrying Grace Wilton. John Budge’s mother’s maiden name was Burnaford and the first witness, Peter Burnaford, would have been a member of the family. The same Peter Burnaford witnessed John Budge’s first marriage in 1770. John Budge had married Sarah Barrett in North Hill in 1770 and they had four children before her death in 1774. Sarah died about a month after the birth of her last child and it may be that her death was attributable to the birth. |

|

|

|

Grace made her mark with the letter “G”, being unable to read and write beyond signing her name with a single letter. Richard Trehane, the second witness, would appear to have been a friend of John Budge. Neither John nor Grace had married in the period from 1774 to 1787. This is surprising as John’s surviving three children had been very young when their mother died and it would not have been unusual for John to have sought out a wife for himself and stepmother for his children. Grace, similarly, had her young daughter to consider but seems not to have gone in search of a breadwinner. Grace had two sons with John Budge. The first was Edward Wilton Budge who was born in 1787 when Grace was almost 40 years old. The second child, Richard, was born three years later but his later life events are uncertain. Any one, or even none, of the following could be this Richard:

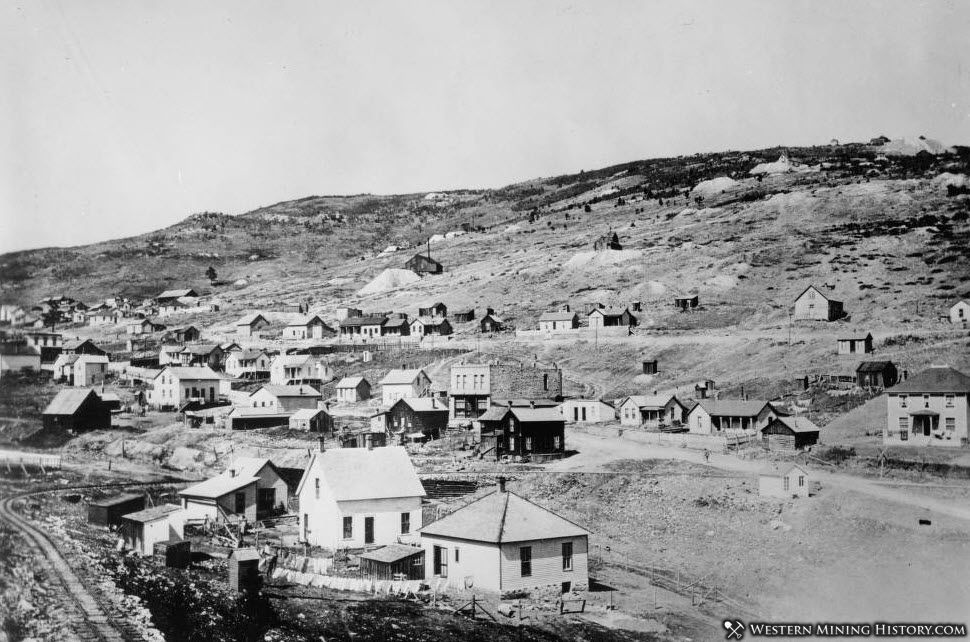

Edward Wilton Budge married Christian Dingley in Linkinhorne in 1809 and they had nine children there before the family moved initially to Mitchell in St Enoder parish before settling in St Erme. Edward was a ‘drainer’ by trade which was a worker who created and cleared drains. These drains are more likely to have been drainage ditches to remove water from boggy fields rather than somebody involved in sewerage which was rare in Cornwall at the time. The work would have required him to move to where there were fields that needed this kind of maintenance and there are wider arable areas nearer to St Erme than would be found on and around Bodmin Moor. Of the nine children two are particularly notable. Mary (born 1816) had two illegitimate sons by two different fathers in 1841 and 1849 by way of evidence that illegitimacy was not rare in the labouring classes. The other person of note was Jane Budge who married William Oates in St Erme in 1844. The fifth of their eight children was Ann Oates (born 1852). Ann married a local man, James Keast, in 1874 and they had four children in St Erme, one dying there as an infant. James and his brother, Henry, decided that the declining economy in Cornwall during the 1870s and 1880s was not as beneficial as the potential offered by working overseas. The background of the major migrations of workers from Cornwall in Victorian times was made up from many factors. Failures of potato and corn harvests in Cornwall in the 1840s resulted in significant price increases which led to severe hardship of the working population. Foreign competition, ironically assisted by the recruited pick of the best Cornish miners, brought about a mining recession and large numbers of mine closures. The copper mining industry virtually collapsed in 1866. Many left Cornwall to escape these hardships as well as reasons such as the payments of taxes. The political situation and some religious intolerance also encouraged emigration. During the exodus of the 1870s the number of miners in Cornwall decreased by about a third and a further third in the 1880s. The usual destinations were the mining areas in North America, Mexico, South America, Australia and South Africa. The Keast brothers chose North America. Henry was unmarried at the time. James took his wife and three surviving children. Work was found in the mines of Russell Gulch in Colorado and the Keasts settled there. The shortest distance between these two places is over 4600 miles. Their journey, undertaken around 1880 would have been over five thousand miles. Whether their fate would have been better served back in Cornwall or by migrating to another location is questionable as there were significant hardships in Russell Gulch, as much as there was elsewhere for the labouring class. Russell Gulch is pictured here in its heydey. |

|

|  |

|

In 1889 James and Ann’s son William Henry was born in August. Two months later James’ brother Henry married Mary Ann Gregor. She had migrated with two of her brothers, Richard and Joseph, from the Padstow area in Cornwall to Russell Gulch. Richard married and had six children but tragedy was never far from the family’s door. Richard died in 1888 as did his one year old son. His wife was expecting their sixth child at the time and he was born after Richard had died. The baby died when just a few months old. These deaths were followed by two more in 1890 when 7 year old Sybil and 6 year old Richard Jesse both died.

James Keast died in 1891 leaving his wife Annie with four children to care for. All these deaths occurred in such a short space of time in Russell Gulch. Russell Gulch was Photographed by Mike Sinnwell in 2006; this image is copyrighted to Rocky Mountain Profiles, where more images may be seen. When the mining industry died in the area the town was deserted and is now a ghost town in the Rocky Mountains with its own website showing tumbleweed blowing along the road. Those family members that had survived the ravages of life in Russell Gulch had long since moved away. There are descendants alive and thriving, many of them in California. |

|

The images at the top of the page show (L-R): Russell Gulch, Colorado; the distance travelled from St Erme to Russell Gulch |